The Perpetual Inventory System

The perpetual inventory system is a system of recording Trading Stock. This may sound quite complicated, but the reality is that if you are in Grade 10, you have already been using the system for a year or two -- only no-one told you that that was what it was called. When we use the perpetual inventory system, we make sure that we record every transaction that affects Trading Stock as soon as we can.

This means that if we buy Trading Stock, we record it in the Cash Payments or Creditors Journal straight away. If we sell Trading Stock, we record it straight away in the Cost of Sales column of the Cash Receipts or Debtors Journal. If we return goods, or have them returned to us, we record the returns in the Creditors' Allowances or Debtors' Allowances Journal.

So what's the big deal?

It turns out that there is another inventory system that we do in Grade 11 (and it's part of the Grade 12 syllabus too), where we don't record all of these things straight away -- but for now we don't have to worry about that. The Perpetual Inventory System is just the name for what we have been doing all along.

Recording Transactions in the General Ledger using the Perpetual Inventory System

This section deals with recording transactions involving Trading Stock in the General Ledger. Note that it covered in Grade 10, and so this section should mostly be revision. If you are comfortable with Grade 10 work and don't want to read this section, at least look at the part on Carriage on Purchases.

The Trading Stock Account

Before we do the all the transactions that affect Trading Stock, it's important that we know what kind of account Trading Stock actually is.

The definition of an asset is (loosely) something that we own or control that will result in future economic benefit to the business. Trading Stock meets these criteria: we will have bought the stock, so we own it, and we will sell it in the future for a profit, which is an economic benefit. So Trading Stock is an asset. More specifically, it is a current asset.

This means that when Trading Stock increases, we will debit the ledger account (because assets increase on the debit side), and if it decreases, we will credit the account.

Something that is also worth mentioning here is that Trading Stock goes by quite a few names. In exercises, tests, and exams, you will be exposed to other names like "Merchandise", "Goods", "Trade Goods", "Stock", or "Trading Inventory". Regardless of the name that they use in the transaction, at school we always call the account "Trading Stock".

Opening and Closing Balances

Because Trading Stock is a current asset, and thus a Balance Sheet account, we will have a closing balance at the end of each period. At the start of the next period, we will have an opening balance representing the value of all the Trading Stock that the business actually owns. This means that usually when we do a Trading Stock account, we will have an opening balance. Because it is an asset, the opening balance will be on the debit side of the General Ledger account.

Buying Trading Stock

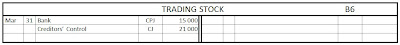

In order to have Trading Stock to sell, we first have to buy it. When we buy stock, we increase the amount of Trading Stock we have, and we thus debit the ledger account. At the end of the month when we post the journal totals to the General Ledger, our Trading Stock account might look something like this:

|

| Buying Trading Stock |

In the example shown, we have bought R15 000 worth of Trading Stock for cash, and R21 000 on credit. We could also increase Trading Stock in a couple of other way -- debtors could return stock, which we'll look at later, or the owner could give stock to business as a capital contribution, or we could buy stock using petty cash.

Paying for Carriage on Purchases

We also look at Carriage on Purchases in the Manufacturing Accounts section.

Carriage on purchases is the cost of transporting trading stock from our supplier to our business. Because it is required for us to actually have the stock in a condition that we can use, we include it as part of the cost of the Trading Stock. This means that when we pay for carriage on purchases, we add it to the Trading Stock column of the Cash Payments Journal straight away (or to the column in the Creditors' Journal, if we use credit).

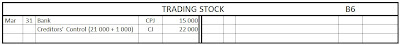

This means that, in the General Ledger, there is no actual indication that we've paid for carriage on purchases at all. For example, if in addition to the purchases made earlier, we also pay R1000 for carriage on purchases, our ledger account will now look like this:

|

| Paying for Carriage on Purchases as well as buying Trading Stock |

In tests and exams it's a good idea to put the (21 000 + 1 000) in brackets next to Creditors' Control, as it helps the marker see where you got your figures.

Basically, when it comes to carriage on purchases, we just treat it as though we are buying some more Trading Stock.

Selling Trading Stock

The whole point of Trading Stock is to sell it. You should all be familiar with the double transaction that happens when we sell stock (for cash):

- We receive money from our customer, which increases Bank on the debit side. Because this money is income, we also increase Sales on the credit side.

- We give Trading Stock to the customer. This decreases Trading Stock (we credit the account) and the contra-account is Cost of Sales, which we debit because it's an expense.

In the general ledger, the cash transaction looks like this:

|

| Selling Trading Stock for cash... now with added arrows! |

If we sell on credit, i.e. we sell to a debtor, the only difference is that Debtors' Control increases instead of Bank:

|

| Selling Trading Stock on credit |

Trading Stock returned from Debtors

If debtors return goods to us, there are a couple of steps to go through. The first thing to remember is that when debtors return goods to us, it's the opposite of a credit sale. In the general ledger, the transaction will look like this:

|

| Return from a debtor |

Remember that returns from debtors are recorded in the Debtors' Allowances Journal.

Returning Trading Stock to Creditors

If the business returns goods to one of creditors, two things will happen: trading stock will decrease, as we are giving some of it back, and we will owe our creditors less. If we return goods worth R10 000 to our creditors, it will look like this in the General Ledger:

|

| Return to a creditor |

Remember that returns to creditors are recorded in the Creditors' Allowances Journal.

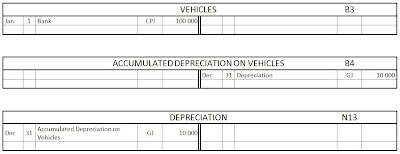

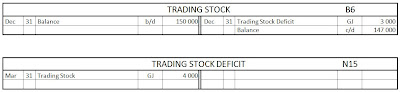

Donations and Drawings of Trading Stock

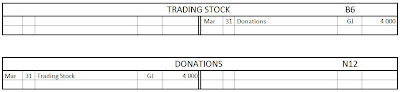

If we donate Trading Stock, we decrease our Trading Stock, and it results in the expense called Donations. If the business donated stock worth R4 000, the transaction will look like this in the general ledger:

|

| Donation of Trading Stock |

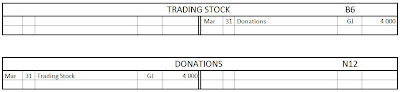

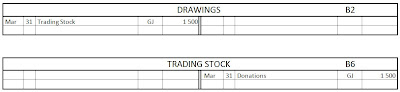

If the owner withdraws Trading Stock for personal use, we credit Trading Stock to decrease it, and we debit Drawings:

|

| Drawings of Trading Stock |

Note that the General Journal is used for both of these transactions.

Year-end Transactions for the Perpetual Inventory System

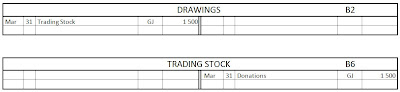

Trading Stock Deficit

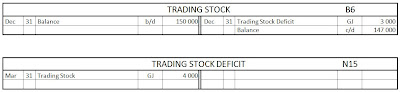

At the end of the financial year, the business will perform a stock-taking. This is when the business physically counts all of its inventory to confirm that it actually exists. The theoretical amount (in the General Ledger) and the actual amount shown by the stock-taking are going to disagree, because stock is likely to get stolen or damaged during the year, and obviously this is not necessarily recorded.

This means that our recorded, theoretical amount of Trading Stock is more than the actual amount of Trading Stock. To take this into account, we decrease Trading Stock until the closing balance is the same as the stock-taking amount, and we create an expense called Trading Stock Deficit to record this decrease.

For example, suppose that at the end of the year, our balance in Trading Stock is R150 000. Stock-taking reveals that R147 000 worth of stock is on hand. This means that there is a R3 000 discrepancy, which we take into account as follows:

|

| Trading Stock deficit at the end of the year |

Note how the final balance is the same as the amount revealed by the stock-taking.

Sales

At the end of the year, we close Debtors' Allowances off to Sales. Note that some textbooks suggests closing Debtors' Allowances off to the Trading Account instead. It makes no difference in the end, but check with your teacher which method he or she prefers.

<<<>>>

Once Debtors' Allowances has been closed off to Sales, we close off Sales to the Trading Account:

<<<>>>

Cost of Sales

At the end of the year, we close off the total Cost of Sales to the Trading Account:

<<<>>>

Trading Account and Profit and Loss

The Trading Account is closed off to the Profit and Loss account. Depending on the type of business, different things will happen from here: (note that final transactions for different types of businesses are covered elsewhere in more detail)

- Sole Trader (Grade 10): All other incomes and expenses are closed off to the Profit and Loss account. This is then closed off to the Capital Account.

- Partnerships (Grade 11): All other incomes and expenses are closed off to the Profit and Loss account, except for the partners' salaries and their interest on capital. The Profit and Loss is closed off to the Appropriation account. See the posts on partnerships for more details.

- Companies (Grade 12): All other incomes and expenses are closed off to the Profit and Loss account, except for Ordinary Share Dividends and Income Tax. The Profit and Loss account is then closed off to the Appropriation Account. See the posts on companies for more details.